Munich While Europe is still debating how to strengthen the domestic semiconductor industry, construction workers in the rest of the world are already moving to pull up new chip factories. The industry in Germany and France is therefore sounding the alarm.

“A joint European effort is urgently needed to strengthen the semiconductor industry in Europe,” says Siegfried Russwurm, President of the Federation of German Industries (BDI).

The situation is dramatic, as the former Siemens executive Board warns. “Due to the acute shortage of chips, the German economy had to cope with a loss of sales of 1.6 percent of German gross domestic product last year,” says Russwurm. That would amount to more than 50 billion euros that companies have lost because semiconductors are missing.

There is no improvement in sight, on the contrary: “With the digital and ecological transformation, the global demand for semiconductors will continue to increase massively,” explains Russwurm. In a position paper, which is exclusively available to Handelsblatt, the BDI, together with the French industry associations Medef and France Industrie, is now urgently calling for more speed from politicians. The race to catch up with the chips must finally begin, the continent does not want to fall behind.

Intel is the only major chip company to have announced its intention to invest in the EU. The Americans want to build new factories in Magdeburg and Italy. In addition, CEO Pat Gelsinger has announced plans to open research sites in France, Poland and Spain.

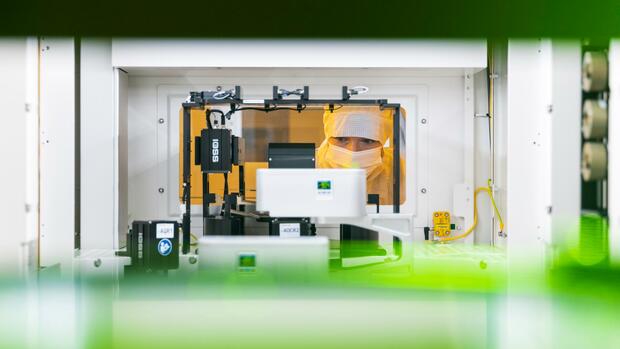

Construction work in Magdeburg is scheduled to begin next year. In 2026, the first wafers, the name of the discs on which chips are produced, could leave the factory. The production facilities are expected to cost 17 billion euros.

For the location in Saxony-Anhalt alone, however, the Silicon Valley company is demanding subsidies of more than five billion euros. The state government in Saxony-Anhalt recently expressed confidence that the state aid will be approved in Brussels. However, the financing has not yet been finally clarified.

The reason: The negotiations between the EU Parliament and the European Commission on the major European funding program for semiconductors, the Chips Act, are not progressing. At the beginning of the year, Commission Head Ursula von der Leyen had presented the project. For example, Europe is to more than double its share of global semiconductor production by 2030 – to 20 percent by then. For this, the production capacity in the EU must quadruple.

Negotiations on the Chips Act continue

The law is an industrial policy offensive. The EU wants to make up for Europe’s backlog in other regions and reduce dependencies on individual Asian suppliers such as the contract manufacturer TSMC from Taiwan. 43 billion euros in state funds are to be mobilized.

In order to achieve this goal, Brussels wants to interpret the previously strict rules on state aid more freely. However, because the EU Parliament has not yet approved the Chips Act, it is still completely open whether, when and on what conditions the billions of funding will actually flow.

Although the EU Commission has basically set the right goal, the industry associations explain. However, it is crucial to release funding quickly and to speed up planning and approval processes, according to the BDI and its French partners. This is the only way Europe can keep up with the chip locations in Asia and America.

Samsung alone invests 340 billion euros

The example of Samsung shows that Europe must not lose any time. The largest chip manufacturer in the world alone wants to invest around 340 billion euros by 2030 – the majority of which in the South Korean homeland. Samsung announced this week. In addition, the Asians are currently moving to a new factory for $ 17 billion in Texas. Among the ten largest semiconductor manufacturers in the world, there is not a single one from Europe.

In the EU, subsidies are probably linked to an obligation, as the Commission’s proposals show. Chip producers who have received state aid could therefore be forced to supply European customers first. With this, the EU wants to prepare itself for supply crises. The industry does not like this at all. The associations warn against planned economy in semiconductors.

The companies also see another problem: Intel will mainly produce the latest generation of chips on the Elbe. The European customer industries, on the other hand, primarily need semiconductors that are produced with more mature technologies. These capacities also need to be promoted, the industry associations demand.

The electronics association ZVEI already warns that the Chips Act is bypassing the needs of European customers. “Europe must strengthen its competence in all structural sizes,” says Managing Director Wolfgang Weber. “Power electronics and sensors are also crucial for the success of the green and digital transformation.“

The European chip companies are the leaders in these fields. Companies such as Bosch, Infineon, NXP and STMicroelectronics produce advanced chips, but not with the most expensive and complex processes, as Intel plans. However, the industry also believes that these factories should be promoted.

According to the draft of the EU, “novel plants” are considered eligible for funding. A formulation that should be interpreted as comprehensively as possible in the interests of European industry. This was also recently demanded by the economics ministers of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg together: “We must not only focus on high-performance chips with the smallest structure sizes.”