It is not yet clear how artificial intelligence should be treated, especially in the future, when the legal regulation of robots is one of the pillars of coexistence.

Dystopian science fiction is full of stories in which robots rebel, take control, ultimately exceed the functions reserved for them. Robotics has not advanced so much that this argument makes sense in the short term, but today already the foundations for legal regulation of robots are being laid, which will influence how your relationship with people in society will be in the future.

When we talk about robots and legal responsibility we tend to think of the machine in a humanoid way that could have freedom of action. It is not necessary to reach these moral extremes for the legal regulation of robots to be a source of controversy. Last year’s ‘We robot’ conference at Stanford concluded that our legal system is poorly prepared. No, they didn’t need to corroborate this at Stanford, but they also shed light on other notable aspects.

Above all, doubts and ideas were raised at the conference. One of the most prominent was whether a crime can be committed by an algorithm and if in that case it should be punished. Leaving aside the most abstract disquisitions, in autonomous cars – a technology about to be marketed-the legal loopholes are highlighted. Who is responsible for an accident? The manufacturer and service provider (data, maps, artificial intelligence) could be accused of negligence if any of their systems failed.

You can go further. Having all the data that the service provider has, if it detects that one of its cars is driving at 90 km / h in an area where it should go at 50 km / h, should the company’s robotic system warn the driver? or should I report it to the police? And if he doesn’t, whose fault is it in the event that something happens? There is no established legal framework for this area, such as neither is there for robotic implants. The contract that you sign with the manufacturer does not differ from the conditions that are accepted when buying an iPad. There are no warranties for unauthorized use. These terms of service may limit a person’s ability to make decisions about themselves.

Blogger and science fiction author Cory Doctorow points out in The Guardian that in the legal regulation of robots, several groups would have to collaborate. In the case of autonomous cars, manufacturers, insurers and legislators should have a voice, as well as consumer rights organisations and engineering associations. He also says that the legislation of this sector cannot be separated from the regulations that frame the software. Not in vain do robots not cease to be constituted by a software that controls a machine.

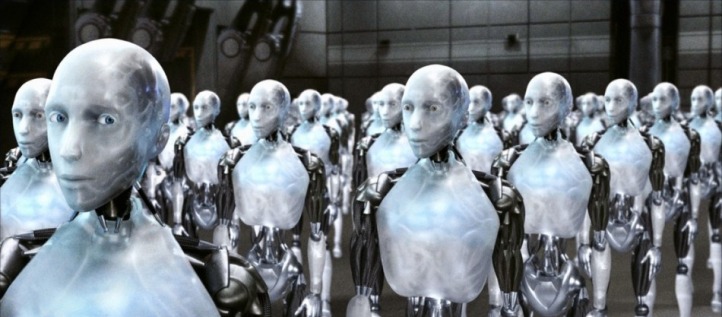

In addition, the blogger brings an interesting reflection on how we see the future of robotics. The most recurrent image is that of humanoid robots performing tasks typical of humans. However, it seems more likely to be one computer that sends instructions to many robotsinstead of everyone having total individual autonomy. A circumstance that is taken to the extreme in the film ‘I, robot‘, inspired by the three laws of robotics proposed by Isaac Asmiov. The wisdom and simplicity of these rules make them a guide for the future, although their foresight is such that they remain anchored in the field of science fiction. In this case what would be expected is the autonomy of the machine to act independently of humans and also its manufacturer.

Robots are nothing but tools

To clear your head of futuristic thoughts it is worth reading the essay published by two professors at the University of Washington in St Louis, Neil M. Richards, an expert in law, and William D. Smart, an expert in computer science, which approaches the issue from its most pragmatic side. In it indicate that the regulation of robots should from the experience we have accumulated legislating on the digital world and technologies.

It is necessary to study what has been failed and what have been the successes to establish a legal framework backed with information, looking for analogies between the technologies of now and the robots that are to come. Professors at the University of Washington emphasize an idea they consider essential. His fundamental conception of robots is that of tools, sophisticated and complex, but whose basic function does not differ from that of a hammer. They explain it in this excerpt from the essay:

“Even when a particular robot has no human form we find it difficult not to project human attributes, such as intentions and motivations into it. Even in research labs cameras are described as’ eyes‘, robots are’ scared ‘of obstacles and need to’ think ‘ about the next step. This projection of human attributes is dangerous when we’re trying to design legislation for robots. Robots are, and will be for many years, tools.”

Image: Richard Masoner / Cyclelicious