The inventor of the Segway new project: the production of human organisera Dragun | 23.06.2020

Dean Kamen founded the Institute of advanced regenerative production (ARMI) is a non — profit consortium of approximately 170 companies, research institutes and organizations in the United States. They make

an annual fee, provide equipment or make other means in exchange for research data. The project is funded by $ 300 million. It remains only to obtain approval

The Federal Agency for food and drug administration (FDA).

Many scientists are trying to grow organs. But a group of Kamena distinguished by the depth of the development — they create tools and mechanisms for mass production, if the FDA will approve them for

patients. He wants to produce hearts and kidneys almost as much as the factories produce smartphones on Assembly lines.

Kamen says that ARMI will succeed — “be it an organ or a piece of body” — in ten years.

Despite the fact that the industrialization of the production of human organs may sound like the most fantastic bluff since Genghis Khan, at Kamena anything can happen.

Kamen turned to the project of artificial organs four years ago. It was then that he met Martina Rothblatt. After Rotblatt daughter was diagnosed with pulmonary arterial

hypertension, she founded United Therapeutics, a biotechnology company that developed drugs to treat it. Rotblatt told Kamen that in addition to pharmaceutical drugs it

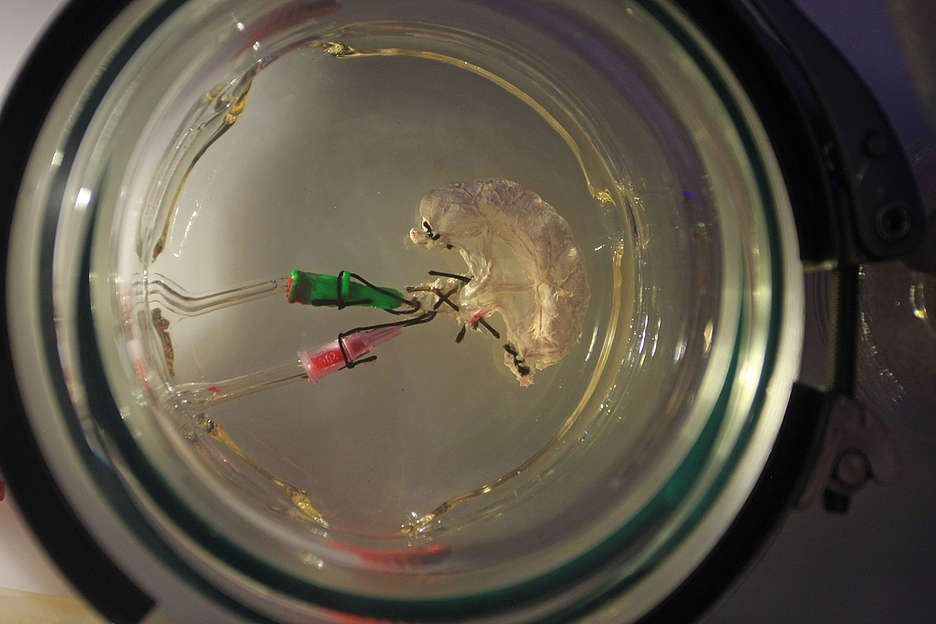

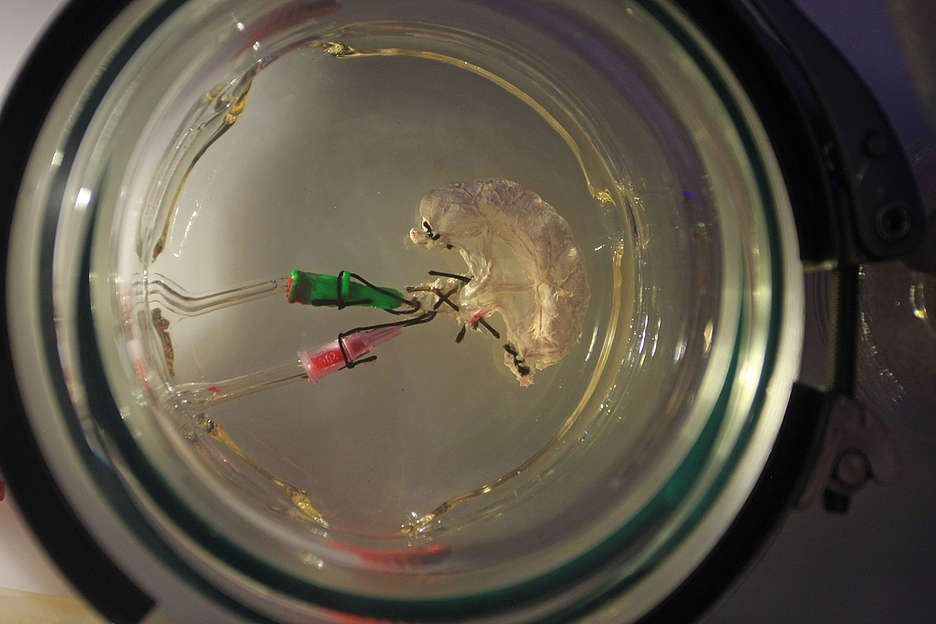

a research group working on growing artificial lungs from stem cells of patients sentenced to death. He visited the laboratory of UT to verify this. There he was

struck by just how outdated the equipment was in the laboratory. He said Rotblatt that can add sensors and systems to improve accuracy and preservation of sterility.

Over the past 15 years have seen impressive progress in growing organs. One of the most interesting events happened in the Institute of regenerative medicine faculty of medicine University Wake

Forest. There, in 1999, Anthony Atala, MD, raised a bladder and implanted the patient. Since then, he has refined the technique, which, like artificial lungs UT

includes the creation of the frame of the bladder.

However, many internal organs have yet to grow in the lab, not to mention placing them in the patient; even the bio-engineering of most tissues, such as muscles and ligaments are still

is at an early stage of research.

Betting on the success in growing bodies, Kamen compares the scaling of production with how Silicon valley has transformed the discovery of semiconductors in the industry of smartphones. “I thought

why don’t we do the same for living tissue,” he says. “There must be a way to get a lot of them, of high quality and at a realistic price for a society that desperately needs bodies.”

Stone knows there are doubters. Throughout his career he paid them little attention. “It will take 50 years? Definitely not,” he says. “Whether it’s 25? Five?”. He makes his bet

that within 10 years, the replacement of defective organ or part of the body will be as a usual practice, as in many standard medical procedures.

Of course, he was so optimistic 20 years ago with the Segway. But since then, he’s learned a lot about the art of collaboration and how to inspire strong players who can take this forward

concepts and to bring them to life. Anyway, the Segway has only strengthened him itching to reach seemingly impossible goals.

the future of medicine