Munich was small yesterday: when Rohm CEO Isao Matsumoto talks about his plans, there is no sign of Japanese restraint. “We want to become one of the big players in our market and play a significant role globally,” the chip manufacturer’s CEO told Handelsblatt.

The manager thus opens the hunt for the Dax group Infineon, the world’s largest car chip manufacturer. On the one hand, Matsumoto wants to grow strongly outside Japan, especially in Europe, Infineon’s home market. On the other hand, he sees the greatest opportunities for the group from Kyoto in business with the automotive industry, the most important revenue generator of the Munich rival.

An advantage over Infineon: Rohm produces silicon carbide (SiC), the chip material of the future, in its own factory of the subsidiary SiCrystal in Nuremberg. With semiconductors made of SiC, electric cars consume less electricity, which is why the raw material is scarce and in demand worldwide.

That’s not all: Rohm only obtains ten percent of its chips from contract manufacturers. Infineon, on the other hand, has around 30 percent of all components produced by suppliers. This has been a hindrance for a long time, because these so-called foundries in the Far East can no longer cope with the flood of orders, long delivery times are the result.

The company’s own deep value creation, on the other hand, ensures a stable supply to Rohm customers, CEO Matsumoto emphasized. “Especially in these times, this is a great advantage.” Experts see it the same way: Rohm has successfully positioned itself long before the current problems in the supply chain, says Peter Fintl, chip expert at the consulting company Capgemini.

In some cases, customers of semiconductor manufacturers worldwide have to wait up to two years for their orders. At Rohm, the delivery period is currently between four and six months, according to Matsumoto.

The manager has increased his medium-term forecast these days. So far, he had promised investors a turnover of around 3.5 billion euros for the year 2025. A goal that the Group will already exceed in the current financial year. Now Matsumoto wants to redeem about 4.5 billion euros in three years. In addition, the group’s owner is aiming for an operating margin of 20 percent, up from 17 percent so far.

That Rohm is now igniting the turbo is not a matter of course. For two decades, the turnover of the company, founded in 1954, was sluggish. Only in the most recent financial year, which ended on March 31, were revenues again above the record set in 2000. For example, revenues have skyrocketed by 26 percent to the equivalent of around 3.4 billion euros. However, the operating margin of 15.8 percent was still well below the 34 percent of that time.

Europe is becoming more and more important for Rohm

Things have been going particularly well recently in Europe, home to some of Rohm’s most important competitors worldwide: in addition to Infineon, the French-Italian manufacturer STMicroelectronics is one of them. Here, revenues increased by almost 40 percent. “I am glad that we have grown so much in Europe, but we are far from satisfied,” Matsumoto stressed. The European business accounts for a good eight percent of sales.

In view of the major car manufacturers in Europe, Matsumoto sees a particularly great potential in Europe. For the new financial year, the group’s owner expects sales in Europe to increase by 29 percent, more than twice as much as in the company as a whole. As a result, the region is gaining weight in the Group.

It is no wonder that Rohm is attacking car chips, as it is a dynamic market: according to estimates by Omdia’s market researchers, sales will grow by a good twelve percent per year until 2025. The most important reason for this is that there are three times as many semiconductors in electric cars as in vehicles with an internal combustion engine. In addition, carmakers need additional chips for automated driving and infotainment.

An important business for Rohm is the so-called power semiconductors, which are necessary for the power supply of electric vehicles. They are installed both in the car itself and in the charging stations.

Last year, Omdia’s global business with autochips climbed by 28.6 percent to $ 51.6 billion, according to Omdia. By comparison, the manufacturers produced only 2.5 percent more vehicles than in 2020, which means that the chip companies have sold more and more expensive components.

Last but not least, SiC chips are in demand. At the SiCrystal subsidiary in Nuremberg, the Japanese produce the material for this and sell it to customers such as STMicroelectronics or Infineon. At the same time, Rohm also develops and sells SiC semiconductors itself. With a market share of ten percent, the Asians are the number four among the suppliers of SiC chips.

In 2017, Infineon also wanted to acquire an SiC producer, the US group Wolfspeed. The American authorities banned the deal with reference to national security. Rohm was more far-sighted and bought SiCrystal from Siemens back in 2009.

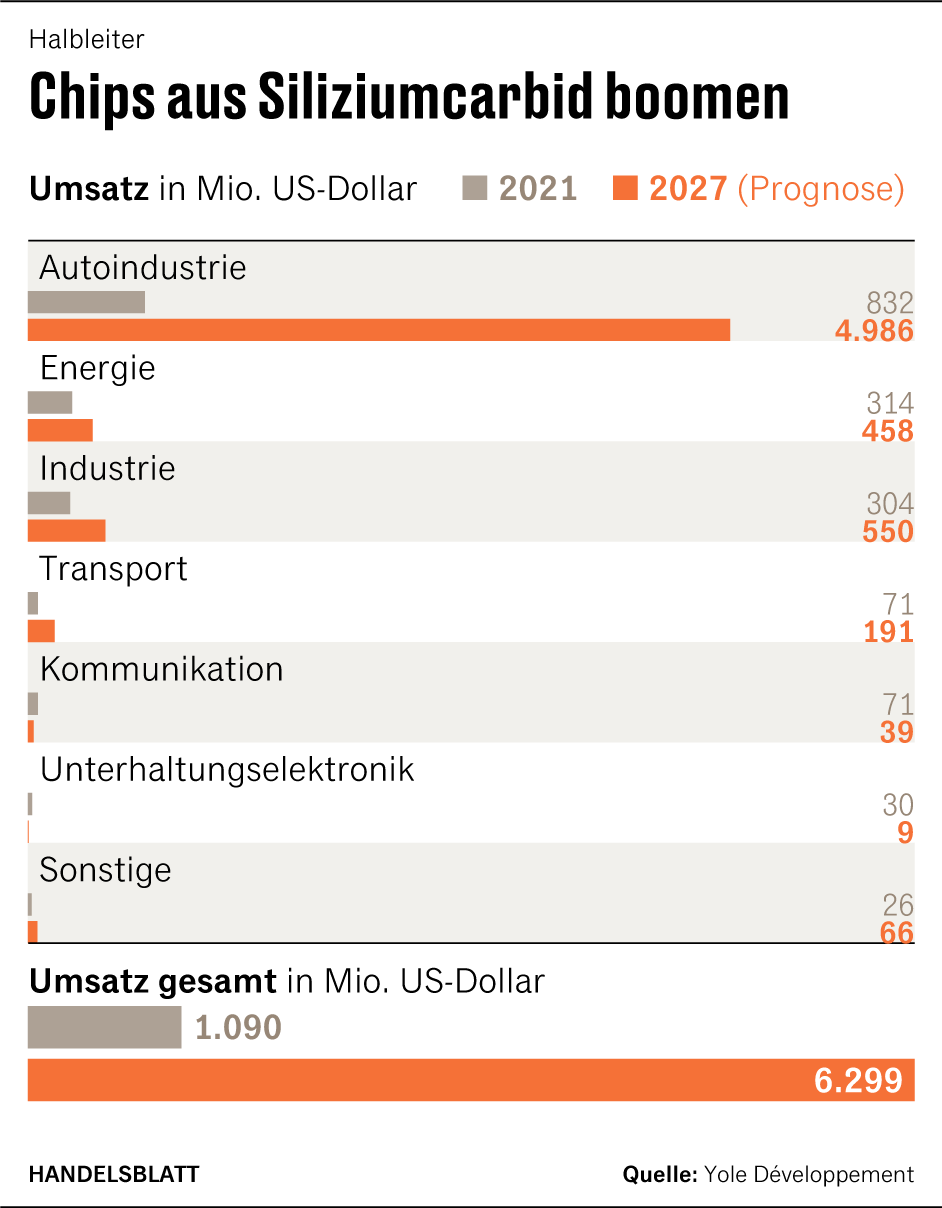

Yole’s market researchers forecast SiC chip sales of $6.3 billion in 2027, about six times as much as last year. This corresponds to an annual increase of more than a third. This growth makes SiC a highly attractive niche in the more than $600 billion semiconductor market.

The combination of silicon and carbon is energy efficient and takes up little space. SiC allows vehicle manufacturers to either use smaller batteries or offer a longer range.

One of Rohm’s best-known customers in Germany is Vitesco, the former drive division of Continental. In the USA, the Japanese supply the electric car manufacturer Lucid, in China the competitor Geely.

“SiC is becoming more attractive due to rising energy prices,” says European Head Wolfram Harnack. The doors in the headquarters of the car companies are therefore increasingly open to him: “There is a strong interest in getting in touch with us directly.“ In any case, the electrical engineer does not have to worry about the supply of the coveted silicon carbide – in contrast to competitors such as Infineon.