Munich does not even have the building permit yet: Intel’s billion-dollar new factories in Magdeburg will not open until the middle of the decade. Nevertheless, Christin Eisenschmid is already worried about how she will find enough staff. “The demand is immense,” says the German BOSS of the American chip manufacturer.

The manager suspects that it will not be enough to post job advertisements. “Retraining programs are also very important,” explains the manager. “We have to think of all the possibilities.“ The Silicon Valley group wants to create 3,000 jobs in the state capital of Saxony-Anhalt in the first expansion stage.

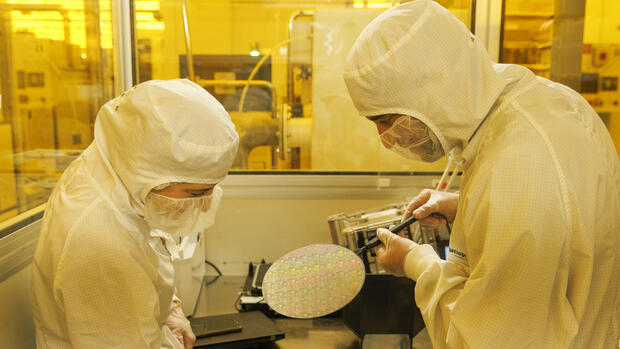

Like Intel, all semiconductor companies in this country are desperately looking for people. The industry needs university graduates in electrical engineering or computer science as well as trained personnel who operate the highly sensitive machines.

Many industries are like that. In the case of chips, however, the lack of employees is particularly critical. The future of German industry as a whole is at stake. Automotive suppliers and mechanical engineers are largely dependent on chip manufacturers from Asia – and they do not supply nearly as many components as the companies need. Again and again the bands stand still.

With a large–scale support program, Europe is therefore to more than double its share of global semiconductor production by 2030 – to 20 percent. At the beginning of the year, EU Commission Chief Ursula von der Leyen presented the plan. 43 Billion euros in public funds are to flow.

The battle for the chip specialists rages in Saxony

The companies are happy to take the money. Intel is collecting almost seven billion euros for the settlement in East Germany. However, it is uncertain whether there are enough employees to put Europe back on the map of the semiconductor industry.

Example Dresden: The chip manufacturers in the Saxon state capital advertise for applicants with large-scale posters. The region is Germany’s number one semiconductor location. Well-known names such as Bosch, Infineon and Globalfoundries manufacture here. No wonder that a battle for specialists is raging in Saxony.

This is a particular challenge for chip start–ups – i.e. those companies that could one day become corporations such as Intel or Infineon. “The universities in Germany are setting the wrong priorities,” complains Aron Kirschen, CEO and founder of Semron. “Far too few microelectronics and mathematicians are being trained.“

As for Nvidia in graphics processors, this is to become the Dresden-based start-up in chips for artificial intelligence. Nvidia is the most valuable semiconductor provider on Earth. The chips from the company Semron, which was founded two years ago, are supposed to be particularly energy-saving. Kirschen’s small team is developing a component that can both store and calculate. This is to ensure low power consumption, because the data does not have to be constantly sent to the central computers.

The entrepreneur wants to more than double his team to a dozen people by the end of the year. The personnel search takes a lot of time and thus resources, which Kirschen would rather put into product development. “We could be much faster if we got enough suitable staff,” he says.

Little competition among graduates

According to him, not only candidates are missing. Many young people are not very motivated. “The European applicants can now choose the jobs. There is no competition among each other.“ If you are looking for a job from nine to five, you are out of place at a start-up like Semron.

The requirements are high – and the image of the industry needs to be improved. Compared to other tech sectors and the automotive industry, the chip industry is not very productive as an employer, according to the consulting firm McKinsey. Strengthening one’s own brand could be a first step for companies to change this. “Companies may also need to review compensation, learning and development opportunities to ensure they are on par with companies in other industries,” the experts said.

The situation will not improve in the foreseeable future. “There are too few new talents coming in,” says Alfred Hofmann, spokesman for the newly founded Bavarian Chip Alliance. The initiative, launched by the Free State, is intended to promote the semiconductor industry in Bavaria.

Bavaria’s Minister of Economic Affairs Hubert Aiwanger considers the industry to be crucial to counter the shortage of workers in other areas. Chips are essential to drive automation forward – the most important answer to the scarce staff in the eyes of the politician.

It is worrying that many experts in chip design will retire in the next few years, warns Intel manager Eisenschmid. They are the basis for the entire industry. Therefore, it is important to “massively build up competencies in chip design” in Germany. In Bavaria, they are currently considering setting up their own design academy.

One thing is clear: semiconductor companies need more and more people. The industry association Silicon Saxony estimates that around 100,000 people will be working in the microelectronics and communications industry in Saxony alone by 2030 – 27,000 more than today.

The Federal Association of German Industry (BDI) is calling for special courses of study for chips – and on a large scale. According to the BDI, a new semiconductor factory would normally employ around 2,000 highly qualified people. In order to achieve the goal of 20 percent global market share, Europe needs a whole armada of additional factories – the Intel location in Magdeburg is just the beginning.

In addition, it is important to attract experts from other parts of the world, says the BDI. Founder Kirschen, however, believes that this is not expedient: “Germany has a demographic problem, and we cannot solve this in the long term by immigration of top specialists or automation.“

The reason: “Other countries will also be able to automate – and the potential that has been freed up will then be invested in innovations for which we lack the talents here.“

For the young entrepreneur, there is no way around a quick and decisive shift at the universities: towards microelectronics.