Düsseldorf, Brussels The European Union’s plans for a new satellite network are becoming more concrete. The satellite network is designed to bring secure and fast Internet even to the most remote regions of Europe. The EU wants to become more technologically independent with the project. Especially in Germany, the program is also seen as an opportunity to strengthen young private space travel.

Now it is clear: with the six billion euro program, one third of the order volume is to go to start-ups and small and medium-sized enterprises. This applies at least to subcontracts with a volume of ten million euros or more. The EU member states have agreed on this. But politicians and the start-up scene are wondering whether the deal actually keeps what it promises.

Bavaria’s Digital Minister Judith Gerlach welcomed the quota: “This is a good signal, especially for the Bavarian aerospace industry,” said Gerlach, referring to numerous “highly innovative start-ups” and small companies from her state.

The Munich-based satellite manufacturer Reflex Aerospace, among others, could be hoping for orders. Isar Aerospace from Munich and Rocket Factory from Augsburg are developing rockets that would be suitable for maintenance work. Mynaric from Munich has positioned itself as a provider of laser communication in such a network.

But the companies are skeptical: “The satellite program reads as if it were once again designed for the big companies. Small companies should be supplied with subcontracts,” says Daniel Metzler, Head of Isar Aerospace.

From his point of view, it would be better to split the budget from the outset or to let old and young companies compete against each other in a development competition. In the USA, several companies initially receive the same order for such procedures. Only at a certain milestone is it decided who will win the entire order.

Is France only interested in its own interests?

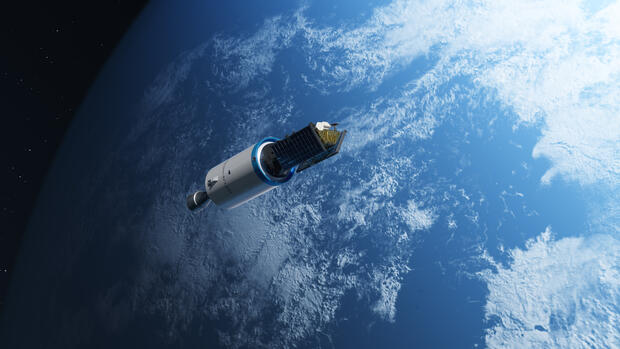

The new EU satellite network, like the Starlink set up by US billionaire Elon Musk, is intended to ensure a nationwide supply of Internet services. In Ukraine, Starlink is currently ensuring that domestic soldiers can exchange data with commanders even on remote front sections. In industry, it enables new business models such as autonomous driving. Industry experts warn of a dependence on US suppliers.

In any case, the network should be built and operated. But the question remains: by whom? In particular, EU Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton is suspected in Germany of wanting to supply established suppliers from his native France with orders – an accusation he rejects.

The commitment of the French Presidency also reinforced the impression of primarily national interests. Rocket manufacturer Ariane Group and satellite manufacturer Thales Alenia Space have the best contacts with decision-makers in Paris and Brussels.

Germany and Italy, on the other hand, came out in favour of small and medium-sized enterprises in the space sector with a position paper. “We have to join forces across Europe – and make sure that German and Bavarian companies are taken into account,” Bavaria’s Digital Minister Gerlach told Handelsblatt.

Distrust of established companies

Although the program now emphasizes that “the use of innovative and disruptive technologies as well as new business models of new space companies” should be maximized. But start-up entrepreneurs know the loopholes from experience.

“It is very positive that the importance of the innovations developed by new space companies is so strongly emphasized,” says Thomas Grübler, who offers infrared images from space with Ororatech. “However, the EU must now ensure that the large system houses actually implement the cooperation with new space companies.“

In the background, several entrepreneurs refer to previous quotas for subcontracts, for example for the Galileo satellite constellation. Often, prime contractors would nullify the quota by defining their requirements in such a way that no start-up could meet them.

A point at which the French interests become clear: satellites should be launched “if possible” from the territory of the Member States. Specifically, this means: from the French overseas department of French Guiana. No other Member State has a launch pad. “The restriction is semioptimal, because, firstly, France has a lot of political levers, and secondly, it will limit the possibilities of carrying out more launches,” says Thomas Oehl, who is involved in several new space companies with his venture capital firm Vsquared Ventures.

Metzler, a rocket manufacturer, expressed a similar opinion: “If it is only allowed to launch from French territory, this would be an unnecessary self-limitation.“ He is also critical of the fact that France would have a right of veto in this regulation. Oehl and Metzler are in favour of making launches from Norway possible on an equal footing.

Parallel to the Member States, the EU Parliament is currently working out its position. The Green politician Niklas Nienaß wants to work there to ensure that European citizens benefit above all and that broadband Internet finally becomes available everywhere. In addition, the service should be much cheaper than Starlink.

“The current proposal would allow this, but does not set explicit incentives. That’s too vague for me,“ says Nienaß. “The European Union must not just hope that the economy will launch appropriate offers. She must actively ensure this.“