Munich The small plant manufacturer Stela is a successful example for the robot manufacturer Kuka. Stela had purchased its first welding robot more than 20 years ago, at that time a bad purchase. “It stood around for a few years, then it was dismantled,” says Thomas Laxhuber, now head of the medium-sized company. The reasons: lack of repeatability, reprogramming too complicated, the workforce skeptical.

But even before the company’s 100th anniversary, Stela had dared a new attempt and purchased a model from Kuka. The programming no longer has to be handled by a specialist, the best welder in the house can do that. Thomas Laxhuber, grandson of the company founder, is satisfied in view of the full order books: “We need the machine to create the production at all.“

Kuka had long lacked the right products to tap into new customer groups – an innovation crisis. “We had not invested purposefully enough,” CEO Peter Mohnen told Handelsblatt. The robots in the premium segment were too complicated to attract medium-sized customers outside the automotive industry. This was corrected and a total of 25 new products and variants were launched on the market during the pandemic. “Now we want to become the number two in the medium term and the world market leader in the long term.“

Kuka is currently in third place behind Fanuc and ABB, roughly on par with Yaskawa. According to industry estimates, the market share for articulated arm robots is in the low double-digit range.

In 2020, Kuka’s sales had fallen sharply due to corona and homemade problems, the bottom line was a loss of 95 million euros. The turnaround was achieved last year. Revenues increased by 28 percent to EUR 3.3 billion. Although the operating margin was still low at 1.9 percent, the Augsburg-based company was back in the black.

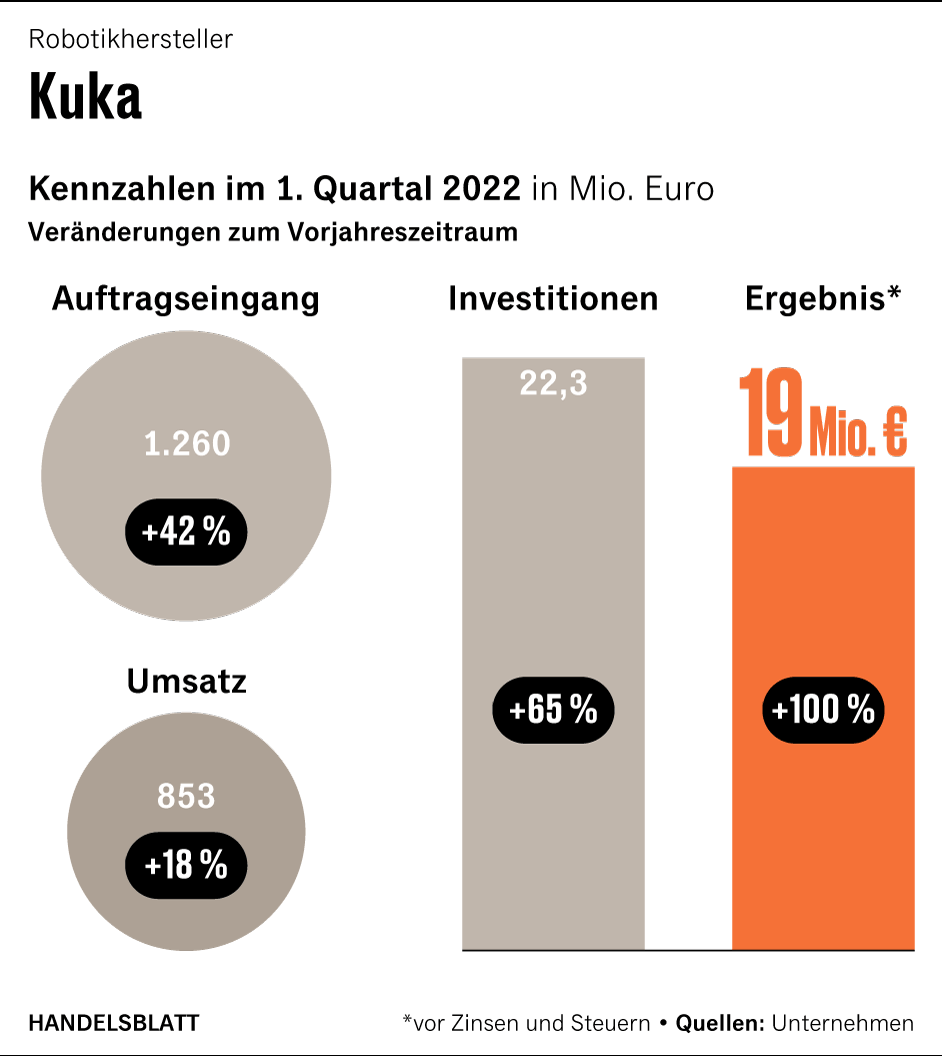

The trend continues. In the first quarter, sales increased by 18 percent to 853 million euros, while operating profit improved from eight to 19 million euros. “We have achieved the turnaround and want to continue to gain significant market shares,” Mohnen is convinced.

More growth in the market, more competitive pressure

The former CFO had taken over the chairmanship of the Board of Management after the takeover by the Chinese Midea and reorganized the innovation management. “We had to innovate faster and involve customers in the development process much faster,” he says.

He is annoyed, for example, that Kuka launched a collaborative robot relatively early on the market. But it was not possible to sell large quantities. Too expensive, too heavy, too complicated to operate was the first litter of the Augsburg-based company, which was especially tailored to automation-experienced major customers with complex requirements.

Cobot pioneer Universal Robots now holds 50 percent of the global market. The Danes have just launched a larger model on the market, making it even more competitive with manufacturers of heavy industrial robots such as Kuka, ABB and Fanuc. “This is an enormously big step for us,” Universal Robots CEO Kim Povlsen told Handelsblatt.

This can be understood as a challenge to the established competition. The Cobot segment and the classic industrial robots are growing together. Universal Robots is building larger cobots, and ABB and Kuka are pushing into the business of small, collaborating robots.

Mohnen is convinced that Kuka can still play a major role in this: “We will catch up.” Kuka has now launched the lightweight robot Iisy on the market. In the next few years, starting with the cobots, all models of the group should get a uniform operating system, simple programming should become the standard.

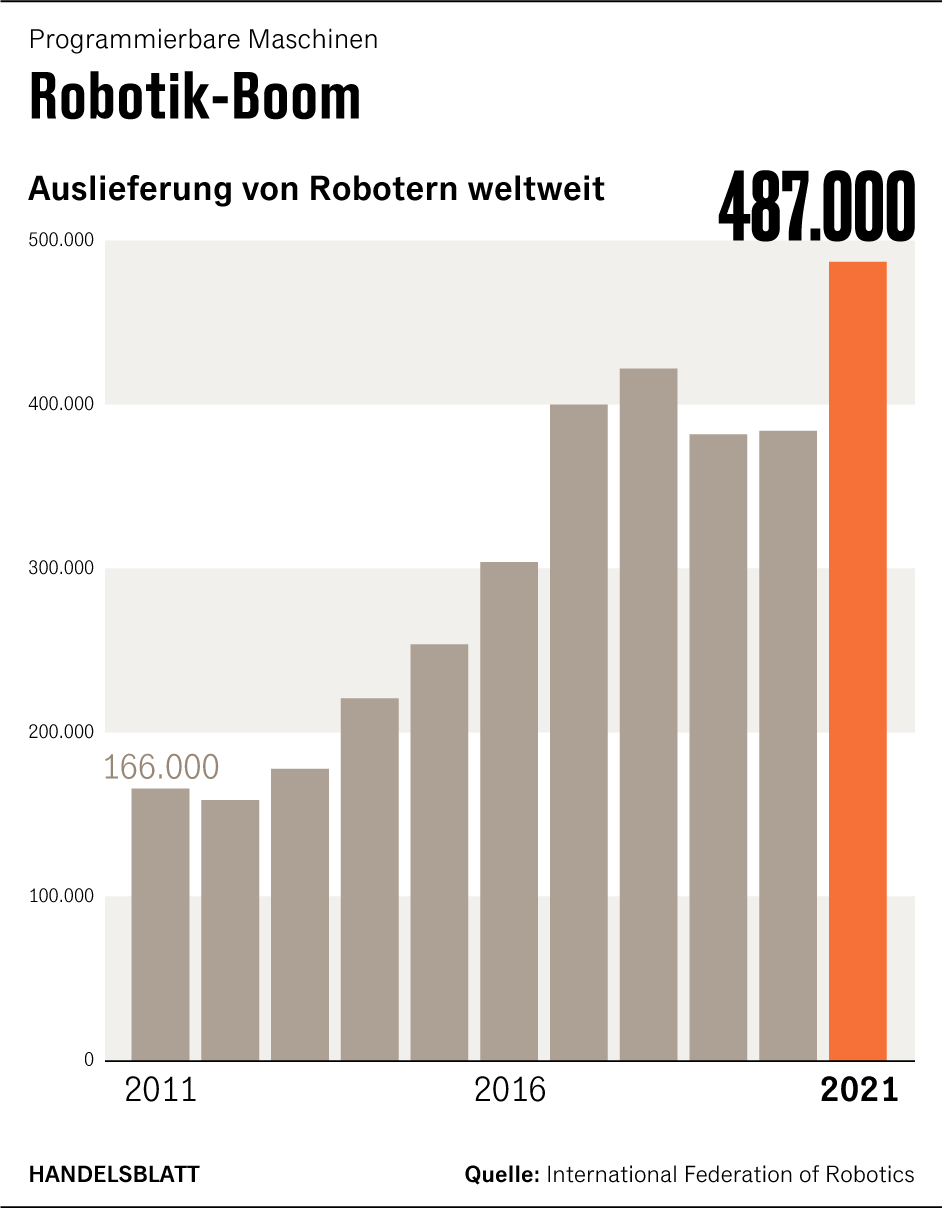

The market environment is currently favorable despite all global uncertainties. Global robot sales rose by 27 percent last year to 487,000 deliveries. “There is now a massive investment in automation,” says Susanne Bieller, Secretary General of the World Industry Association IFR.

The robotics industry is benefiting from several trends. During the corona pandemic, automation helped many companies to maintain production. Because of the problems in the supply chains, many companies also want to bring production closer to home. However, due to the shortage of skilled workers and the high wage costs, this will often only be possible with the help of robots.

Stela Laxhuber is a good example. The new robot takes over the welding of the fan wheels for drying systems, for example for the food and paper industries. “The work has to be done very precisely, but it is monotonous; a bad combination,” says Laxhuber. Qualified specialists are difficult to find. And so now the robot does the job in 50 minutes. Welding by hand previously took five hours.

The role of China

The first robot from Stela had to be trained again and again for each order. Now only the initial installation was complex, according to Laxhuber. “There was blood, sweat and tears.“ The operation is now functioning smoothly. Successes of this kind nurture the hope of Kuka and the entire robotics industry for the new business outside the core automotive industry, which often failed due to the complexity.

The second major growth area, despite all the geopolitical tensions, is China. For Kuka, the People’s Republic is important in many ways. The takeover of the Augsburg-based company by Midea six years ago has met with a lot of criticism. A takeover of a key technological company by a Chinese investor would be hard to imagine in the current environment.

With Midea’s help, Kuka also wanted to improve its position in the Chinese market, the most important in the world. But here Kuka progressed more slowly than planned. Last year, sales in China were around EUR 590 million. At the time of the takeover, the then Kuka CEO Till Reuter had already promised revenues of one billion in China for 2020.

But even Midea plant managers were reluctant to use the expensive Kuka robots. While other companies are concerned about a China cluster risk, Kuka’s China sales are still lower than those in the USA, of all companies. “Last year, Midea helped us to achieve a boost in China for the first time,” Mohnen explains.

In the meantime, Kuka has robots on the market that are better adapted to the special needs in China. For example, customers in the electronics industry who are new to the field of automation use small robots such as the Delta. Midea is now also increasingly using Kuka robots in its own home appliance factories. In addition, Kuka benefits from the owner’s customer and logistics network.

In Augsburg, many are still skeptical about the influence of the Chinese owner. The penetration could become even stronger if Midea takes the German subsidiary off the stock exchange soon. This does not change anything operationally for the company, Mohnen emphasizes. The Chinese had promised further guarantees in the course of the step, and nothing should change in governance as a result of the squeeze-out. There are still independent representatives on the Supervisory Board.

In addition, around 800 million euros are to be invested in research and development by the end of 2025, three quarters of which will be in Augsburg. The new operating system has also been completely developed in Germany. In this way, Kuka wants to ensure that it remains a German company at its core.