Stuttgart, Munich, Düsseldorf Marc Alber has had to send a courier service from one minute to the other to Stuttgart Airport for almost two years. If a shipment of semiconductors arrives unexpectedly, the Managing Director of the family business Geze must not lose any time. Without the semiconductors, production at the Swabian specialist for intelligent opening and closing systems for buildings would come to a standstill.

But it costs: sometimes Alber browses 20 times the previous price for the chips – and it is still hard to think of a punctual delivery, even though the family business subjects 90 percent of the supply chain to a risk analysis.

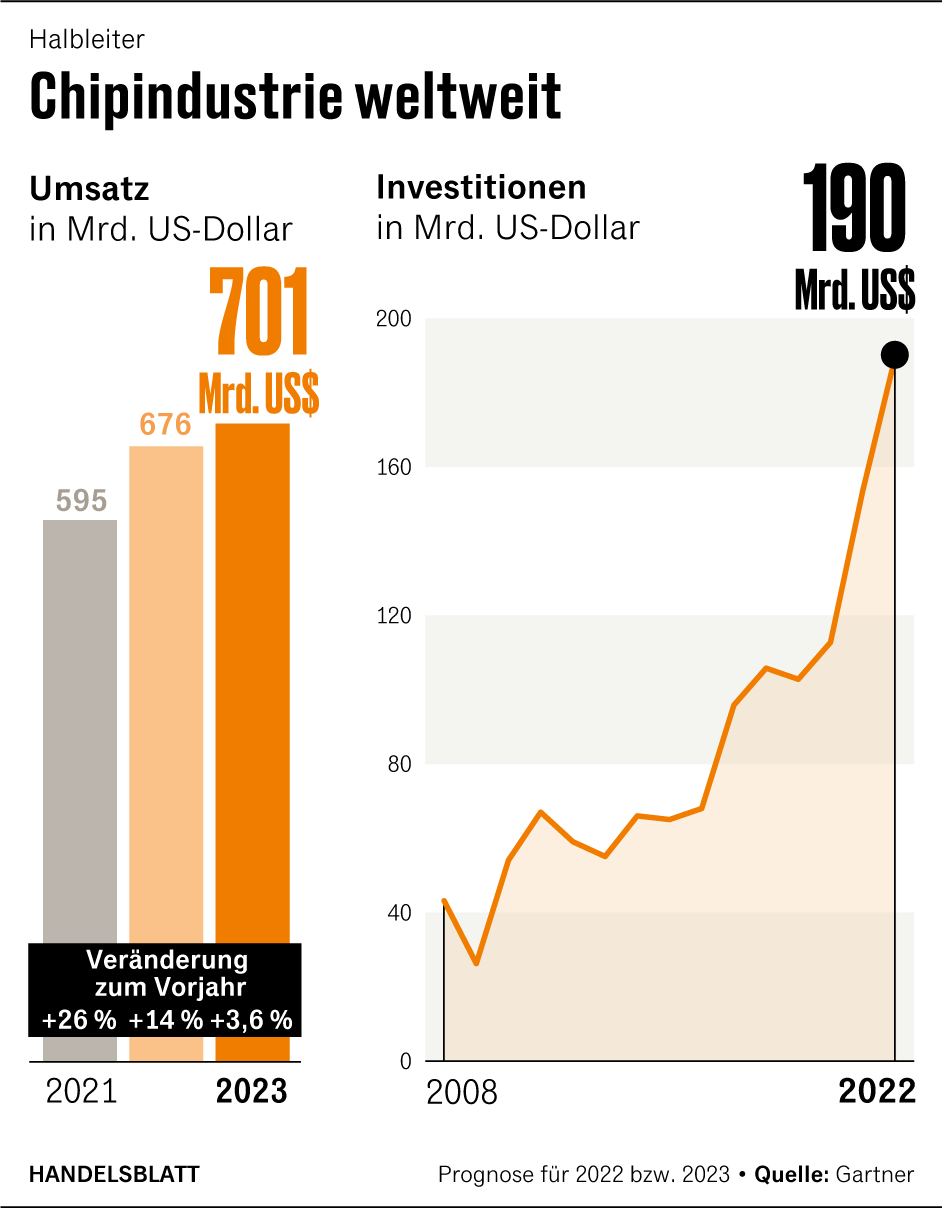

But where there is nothing, nothing can be analyzed. Like Geze, thousands of companies are fighting for a scarce commodity: chips. The pandemic and the associated digitization have triggered a surge in demand that is overwhelming semiconductor manufacturers.

Above all, there is a lack of those components that German industry most urgently needs: chips that are produced with mature processes by contract manufacturers in Asia. In the meantime, TSMC, the number one among the so-called foundries, is building such production facilities on a large scale. Other manufacturers also put billions into factories. But that doesn’t help much at first, emphasizes Peter Fintl, chip expert at the consulting company Capgemini: “The big investments in more mature technologies are starting now. Therefore, it will take a few more years before the supply gap is closed.“ There is an eternal shortage of chips.

A new crisis every week

“Almost every week there is a small or bigger crisis somewhere,” says Rutger Wijburg, Chief Production Officer of the Munich-based semiconductor manufacturer Infineon. Sometimes it’s a snowstorm in Texas that paralyzes production, or a power outage at the most important German chip location in Dresden like last fall. “In the last 30 years, I have not experienced such a disruption of the supply chain,” says the experienced chip manager.

The carmakers are particularly hard hit. The true extent of the chip bottlenecks in the industry is currently only being covered up by the fact that far fewer vehicles are being built than possible and necessary, says Matthias Zink, Member of the Board of Management Automotive Technologies at the Franconian supplier Schaeffler. In addition, customers would currently accept longer delivery times. Zink: “If we go back to the old quantities, the problem would be suddenly more serious.“

An important reason for the run on the components is the boom in electromobility: “The demand for semiconductors in the car has increased extremely,” says Michael Adam, who is responsible for the chips at the car company BMW. In cars with internal combustion engines, chips are installed for 600 euros, in electric vehicles it is 2500 euros.

According to the consulting firm Alix Partners, car chips are likely to remain in short supply until at least 2024. The global capacities in the chip industry would simply not be sufficient to meet the entire needs of the automotive industry, the experts predict.

Waiting for the new Thermomix

But not only car buyers need patience. There is also a shortage of consumer goods. If you order a Thermomix, you currently have to wait ten weeks before the digital cooking machine arrives at home. “At the moment, the global semiconductor shortage is having a major impact,” says Thomas Stoffmehl, CEO of Thermomix manufacturer Vorwerk.

Thermomix Production

Vorwerk has the Thermomix food processor manufactured in France. Layers fail because semiconductors are missing.

(Photo: picture alliance / abaca)

The order books at Vorwerk are also full. 1.5 million units of the cult kitchen machine were sold worldwide in 2021 alone – more than ever before. However, because a micro-controller required for the Thermomix is in short supply worldwide, Vorwerk had to shut down production. At the main plant in France, the production of the Thermomix was throttled, shifts were cancelled at certain points. The longer delivery times may possibly last until autumn, Stoffmehl fears.

>>Read here: Dependent on America: German industry also lacks the guts for chips

Micro-controllers are in great demand around the globe. Last year, for example, manufacturers’ sales of these components soared by more than a quarter to a good $ 20 billion. The leading suppliers, chip companies such as NXP, Microchip or Infineon, did not receive nearly as much goods from the contract manufacturers in the Far East as they would have needed. One of the reasons: they had reserved too little capacity. In 2019, the business had shrunk by seven percent, in 2020 it went down by two percent. No one had expected such a boom.

EBM Papst laments “distribution struggle”

The new boss of the fan manufacturer EBM Papst, Klaus Geißdörfer, now expects a permanent chip crisis. “We got off to a good start in the first two months of the financial year, but we expect massive interruptions in the supply of electronic components again in the next three months.“ The fiscal year began on April 1.

The chip shortage will continue for at least the whole year, the manager fears. The goal of double-digit growth again is at risk. Last year, the turnover of the Swabian family business climbed by ten percent to 2.3 billion euros.

>>Read here: Catching up with chips: New Infineon CEO calls for more speed in subsidies

EBM installs similar components in its fans as the automotive industry does in its electric vehicles. Geißdörfer: “We are really fighting against the big players in the world in the distribution of these products.“

Rapid improvement is not in sight. Semiconductor manufacturers cannot expand their plants at all in the short term. There is a lack of equipment. “The major suppliers are struggling to deliver the machines in accordance with the wishes of the customers,” complains Infineon Board MEMBER Wijburg. “Twelve months delivery time is now common for the tools, 18 months and longer are not uncommon.“

In view of the political tensions between the West and China, the situation could worsen in the future, the manager warns. Some of the major chip manufacturers are located in the People’s Republic, and they also produce on behalf of Western companies. “It could be that China is using parts of its capacity for itself,” warns Wijburg.

Meanwhile, semiconductor customers are taking completely new paths, explains Capgemini consultant Fintl: “The industry is getting better and better prepared for the chip shortage. Due to adapted designs, many customers can now switch to alternatives if a semiconductor variant is not available.“ Necessity is just inventive.